- Even though the gaming TAM looks large on paper, gaming companies have diverse needs. There are nuances that shrink the TAM depending on what types of gaming companies have the hair on fire problem that your product solves

- Based on our ideal customer profile, we had to adopt an enterprise go to market motion which was challenging to get initial traction for

- We needed to truly be 10x better off the bat since we were looking to replace a core function for gaming companies and we couldn't get there

A startup is a long and difficult journey, one that I was wholly unprepared for despite having a decade of work experience in finance and tech. Learnings from one failed startup influence the next startup attempt, so to take a step back and discuss why I got into the gaming space in the first place, I have to talk about my first startup, an investment app that helped people learn about and construct portfolios of ETFs, that I co-founded in 2021.

In this startup, my cofounder and I made every single mistake in the book due to a lack of experience as first time founders. Everything went wrong and when we were just about to quit, we applied to Y Combinator on a whim (our response to why do you want to join YC was “We don't know if we really want to”) and surprisingly, we got in to the Winter 2022 batch. YC was an amazing experience where I learned a ton about how to navigate the tumultuous pre-product market fit stage of a startup. However, we were unable to find product market fit, and the company was acquired in August 2022, leaving me determined to try again using everything I learned in YC.

Why We Chose to Build in Gaming

When deciding what to build next, I had 3 principles in mind:

- B2B is a lot easier on average than B2C because there is a more obvious, tried and true go-to-market motion (outbound sales)

- To pick a space that I was or could be an expert in. This would allow for a better understanding of problems potential customers faced as well as a network to find our first customers

- To pick a space with a large TAM and some evidence that similar-ish companies had previously been successful

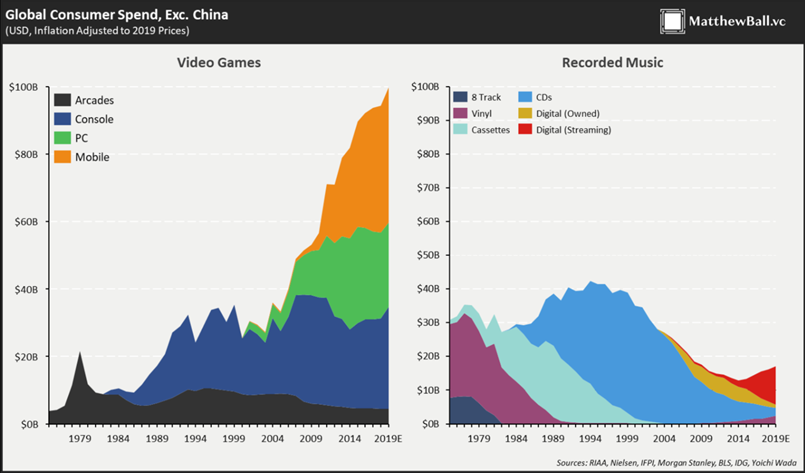

Gaming was a perfect fit for these principles because 1) gaming companies use a lot of tools to build and operate their products 2) I am a huge gamer and previously worked as a product manager at Scopely, one of the largest Western mobile gaming publishers, so I was intimately familiar with problems gaming companies face and had strong founder market fit and 3) gaming was a huge ($100B TAM excluding China) and fast growing market with some previously successful B2B companies like Unity and AppLovin.

What We Built

Now that I knew what sector I wanted to focus on, the next thing to figure out was what type of product to build. Here I drew on my experience working as a product manager running live operations at Scopely.

Live operations is a style of game management that treats a game as a live service and continually delivers new features, updates, sales, in-game events, and improvements to a launched game to improve the experience for players. Most successful free-to-play games, including heavyweights such as Clash of Clans, Genshin Impact, and Call of Duty Mobile, rely on live operations as a crucial component to their business strategy for monetizing and retaining users over a long period of time.

The key to successful live operations is having tools that allow non-engineers to quickly push different event types, such as in-app purchases (IAPs), tournaments, new campaigns, etc, to production. I knew from firsthand experience that these tools were always built in-house and were very difficult and time-consuming to build properly and maintain. Furthermore, poor tooling prevents a game's live operations team from being able to operate at the speed required to successfully hit revenue and retention targets as well as making their lives absolutely miserable. This was the number 1 pain point I had running a live operations team at Scopely (live operations staff would actually quit because they got fed up using our tool) and at many other mobile gaming companies.

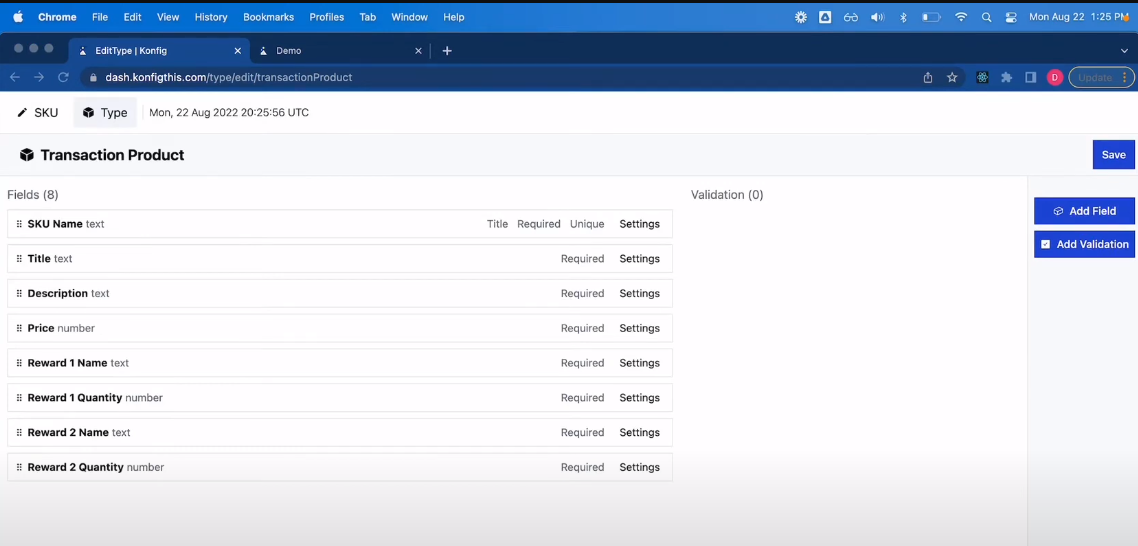

Our vision then was an out-of-the-box live operations tool. We built a specialized headless Content Management System (CMS) that allowed live operations teams to quickly configure and push events to production via a single API. Using Konfig, a game team could create data models representing different types of events (or use ones pre-built by us), populate those models with validated data, and push those events to a single endpoint where the game's frontend could pick those events up and display them in any way they want with any logic that they want.

We even had advanced features such as segmentation that would allow games to customize experiences for certain groups of players.

All in all, I felt that what we had built would have solved my problems as a product manager and, with such a large market, could solve a lot of other people's problems as well.

What Went Wrong

Except that's now quite how things turned out. It turns out that we made three key assumptions that turned out to be false and made it difficult for us to get traction.

TAM is Smaller Than We Thought

$100B TAM with over half of it utilizing some sort of Live Ops strategy seems really large but when we dove in, we realized two things. First, a large part of the TAM was in Asia, and we were not equipped language- or culture-wise to sell to Asian companies. Western gamers in general prefer console games, while Asian gamers were much bigger into PC and mobile games. Given these dynamics, Western game developers chose to focus more on console games, and we found less than 700 total gaming studios outside of China, South Korea, and Japan - not a very promising market to sell into.

The second problem was that not every genre of game wants to run an intense enough of a live operations strategy where they would need strong tooling. For example, hypercasual games like Cat Snack Bar don't expect to retain users for more than 30 days and try to make their money off ads instead of IAPs, so their business model doesn't require live operations. Unfortunately for us, hypercasual and casual games are more popular in the West, while games that would require strong live operations tooling (like RPGs) are more popular in Asia, making our TAM of 700 gaming studios even smaller.

Sales Motion is Enterprise

It is my personal opinion that for most startups it's easier to sell to other startups than to enterprise companies. Hence the meme of YC companies selling to other YC companies to get off the ground.

This is because as a startup you have zero credibility and because the enterprise sales motion is very long and requires buy-in from multiple stakeholders, any of which can kill the deal. So ideally, I wanted to sell Konfig to startups, and I originally assumed there would be many to sell to. From the TAM section, we knew our ideal customer profile was Western developers of more hardcore mobile games, but we found out that most of these games were developed by enterprise sized companies because their development and user acquisition costs were higher than more casual games. This meant that we had to go through an enterprise sales motion to get our original customers.

Although I had some connections to large mobile gaming companies due to my time in the industry and many of the game teams themselves wanted to buy our product, getting in buy-in from the corporate team was much more difficult than we anticipated due to misaligned incentives. This was because many enterprise companies have a central internal tools team that jealously guards their fiefdom even if the product teams complain that the tools don't work well for them. We didn't understand when we started that these misaligned incentives were an organizational reason why the poor live operations tooling problem wasn't being solved.

It's Harder to Convince Companies to Outsource a Core Function

Before starting Konfig, I didn't think too much about whether companies would be more likely to use a third party tool for a core or an ancillary function, but this turned out to be an assumption we should have spent more time thinking about. Through our sales calls, it became clear to us that live operations was considered a very core function that developers wanted to own, so their willingness to outsource it to a third party (much less a startup) was low. We had to be even more than 10x better than any solutions that they could build themselves, and we just weren't able to convince potential customers that we were.

What We Learned

After spending a month and a half building the product, we spent another two months trying to sell it. We got interest from multiple game teams, but the sales cycle bogged down. We realized it was because the people that wanted our tool (live operations teams) didn't have the decision-making power to buy it themselves, and we had to help them convince the corporate teams that were the real key decision makers. This started us down an enterprise sales motion that we were just never quite able to figure out and we were unable to close any deals.

Obviously, something wasn't working, so I sat down with my co-founder to discuss what we should do next. I strongly felt that as a startup with no funding, we had to get initial traction quickly. Our lack of traction meant that it would be very hard to raise venture capital and, more importantly, made me lose conviction that this was a hair on fire problem (if it was, surely someone would want to buy the product even in its MVP form). The relatively small number of potential customers also meant that at scale, we would not be a very big business either unless we had very large contracts, which seemed unlikely to me given that even Unity has pricing power problems. Not finding enough customers is probably the most boring way for a startup to fail, but it's also the most common. And once that happens, I feel it's best to move on quickly and find something better to work on.

Thus, we made the decision to hard pivot out of gaming, and we went looking for an industry that had the opposite characteristics of the gaming industry, i.e. more startups, a larger TAM, and a service that we could provide that was an ancillary part of a business. We eventually settled on making developer tools for API companies to help them easily onboard customers. This time, we got off to a much quicker start, signing our first deal before we had even built the product, and we've continued to be able to grow and raised our pre-seed round over the last year. It's hard to tell where this new line of business will lead in the future, but the biggest learning I've had is that it's hard to know whether your assumptions are true or false a priori because there's a lot of nuance in every industry that you just won't know about until you try to build a business. So the best thing to do is to launch fast and let traction and growth guide your decision on if you need to pivot or not.